Mario Pirovano’s welcomes the audience to his one-man performance of Francis, the Holy Jester as a politician on the hustings. Launching the show with the promise of overturning centuries of misconceptions, he springs into the story of Francis, emphasizing that the real stories of the thirteenth century Italian saint are uniquely wonderful because they show how it is Francis the ‘holy fool’ who realises his life as friend of the poor, champion of the persecuted and heroic worker for peace and justice.

Written and directed by Dario Fo, Francis, the Holy Jester is translated into English and performed by Pirovano for its UK premiere at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival in 2009. As I listen to the opening preamble inside the Italianate-looking Anglican parish church of St Francis of Assisi, West Wickham, I acknowledge that the political motive for Pirovano’s performance of Fo’s play is nothing less than the wholesale discrediting of regressive forces, such as the corruption of a Catholic Church, that notoriously continues to persecute visionaries that threaten the status quo.

In fact, the figure of Francis is symbolic of Dario Fo’s lifetime’s work as a political activist, performer and playwright who, in the words recorded on his award for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1997, emulates “the jesters of the Middle Ages in scourging authority … upholding the dignity of the downtrodden”. Like Mistero Buffo, Francis, the Holy Jester shows how the Church’s anti-theatrical sentiment particularly targeted comedians of the Commedia dell’Arte, forcing them to flee Italy during the counter-reformation. Ironically, the Commedia’s persecution in Italy is Europe’s and England’s theatrical good fortune. For instance, James Burbage noted the presence of an Italian Commedia troupe in the first Elizabethan playhouse of The Theatre in 1576, and English theatre scholars every since have pointed out their influence on Shakespeare’s comedies and, then later, their impact on the development of English pantomime.

Fo’s address at UNESCO’s World Theatre Day in Paris continues on the theme in March 2013 when he points out how reactionary forces always see it as “urgent to rid our cities of theatre-makers” as if they are “unwanted souls”. He explains how he continues to draw inspiration from the Medieval church’s expulsion of Commedia players and urges current theatre-makers to create “a new diaspora of Commedianti, of theatre-makers, who would, from such an imposition, doubtlessly draw unimaginable benefits for the sake of a new representation.”

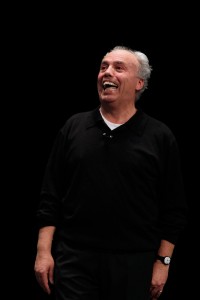

Mario Pirovano’s association with Fo’s company since the mid-1980s makes him an inheritor of its radical stories and Commedia storytelling style, an approach which he seems in no way tiring of, touring Francis the Holy Jester for the past four years throughout the Middle East, East Africa, Sweden, and Norway and on the campuses of Princeton and Harvard in the USA. His 2013 UK tour began in July at the International Medieval Congress in Leeds and concludes here in West Wickham. Quite the contrary, using only a basic lighting rig and one radio microphone, Pirovano passionately shows that nothing matters but the story and how it lives in the storyteller’s physical presence: through gesture, facial expression, body movement and vocal tone.

In watching him, I recall how families of Italian comedians, for instance, the Grimaldi’s in the 18th century and the Leno’s in the 19th and early 20th centuries, became part of a steady arrival of Italian performers who worked with John Rich at the Lincoln’s Inn Theatre and the Theatre Royal, Haymarket, contributing to Rich’s and other London theatre managers’ invention of English pantomime.

Mario, a tall man of 60, pirouettes and carves up the space with gestures and the change of direction of his gaze. With the minimum of fuss, he takes a sideward step to speak in different character voices or locates himself in another part of the stage to show the location of other players in the story. Beginning with the well-known story of how Francis tamed the wolf of Gubbio, the four stories show a forceful Francis throwing himself into religious life with all the physical agility of the jester performing at a fair. For this, he is always at risk of imprisonment, beatings and expulsion by the authorities. It is a theme, which Mario returns to many times during the two-hour performance.

At some point, I no longer to see the difference between Mario the storyteller and Francis the Jester as Pirovano compactly weaves together his own political reflection of European politics and Francis’ rationale for working with ordinary Italians against corrupt Church practices. The story of Francis visiting the Pope is particularly noteworthy in this regard as Pirovano shows Francis seeking permission to preach the gospel to the people in the streets. For his trouble, he is ordered to go and preach to pigs instead. In a fairytale style of coincidental dreams and highly dramatic actions, the story shows how the Pope’s orders backfire on him, as Francis’ sermon to the pigs leads to the good man being caked with animal slops and faeces and, in that state, goes once again to seek further instructions from the Pontiff, this time observed by a whole crowd of people who inadvertently protect him from the Pope’s further punishment.

For me, however, the most remarkable of the show is the one in which Francis delivers a satirical ‘tirade’ in the main piazza of Bologna in an attempt to shame the Bolognese into making peace with the neighbouring city of Imola. Listening to the storyteller present Francis’ sharp wit and piercing observations carries for me the feeling of being literally punched the ironic images which Francis praises maiming and widowhood as the aspirations of all Bolognese people. The story ends with a description of muffled sobs punctuating Francis’ phoney praise the people’s demand that the city authorities begin peace negotiations.

The final story, concerning the day of Francis’ death in October 1226, I am confronted by the farce of archbishops trying to track down a dying Francis to cash in on his religious celebrity status. Meanwhile, Mario shows a sick and stumbling Francis, barely moving and ultimately being carried from place to place, seeking out a peaceful place to die. The agonising journey he makes to his final resting place moves me, as it shows Francis doing everything in his power to thwart the Church from using his own corpse as a holy relic.

Maybe then, I need to admit my own discomfort on hearing the political and religious radicalism of Francis’ Christianity. The power Mario Pirovano brings to Francis addressing a tree full of birds at sunset in the Italian countryside is dynamic, sensuous and real. I speculate what if Francis’ sharp, piercing voice was to address the General Assembly of the United Nations today? Would we be any better able than his contemporaries to embrace his uncompromising performance as a holy jester, as someone who believes that in lowering himself to the position of ‘the fool’, he is able to become the most blessed of all Christendom, the peacemaker?

Mario Pirovano, Storyteller

Mario Pirovano loves to describe how he came to the art of storytelling by a slow, organic process of listening and observing other storytellers. Of course, he didn’t just observe or listen to just anyone. He was uniquely placed to view the everyday workings of two of Italy’s great performers, Dario Fo and Franca Rame.

On first meeting Fo and Rame in London in 1983, he explains, he was a ‘leaf in the wind’ who, like many young Italians, had come to London and was working casual jobs. When he returned to Italy as part of Fo and Rame’s stage crew, he begins to live a very different kind of life, devoted to working on activist political issues through theatre. His theatre apprenticeship involved working as their driver, front-of-house bookseller and then as a performer, only after ten years of observing how the work raised awareness of the plight of the homelessness, the disabled and others marginalized by corruption and injustice of Italian society.

In our conversation for this article, he spoke of his earliest experiences with Fo and Rame’s Milan-based company as responsible for setting up Dario Fo’s book display at every venue in which they performed. Fo, a prolific writer who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1997 for emulating “the jesters of the Middle Ages in scourging authority and upholding the dignity of the downtrodden”, customarily travelled with forty to fifty boxes of books.

As I listen to Mario’s revelation of how all-consuming life was in Fo’s and Rame’s political theatre, I am reminded of other theatre histories of left-wing theatres that portray life not as working in a theatre industry but in organisations that seem not unlike religious communities: for instance, I believe that of Ariane Mnouchkine’s company in Paris and Eugenio Barba’s company in Denmark operate like communities of artists rather than conventional theatre companies.

Today, Mario still continues to hold true the method of storytelling he believes he has come to value so much through his unique apprenticeship. He gently criticises, for instance, those who dress up the art with either too much technology or other effects, and passionately emphasises that nothing matters but the story and how it lives in the storyteller’s physical presence: through gesture, facial expression, body movement and vocal tone.

The relationship of the Italian storyteller goes way back to Shakespeare’s theatre and the Elizabethan playwright’s in general. It’s well document in histories of the travelling Italian troupes of the Commedia dell’Arte, how they either came directly from Italy or via France to England. Later in the Restoration period, Italian companies frequently performed at the Theatre Royal, Haymarket as well as in fairgrounds such as at Southwark, seen in William Hogarth’s well-known Southwark Fair.

Mario Pirovano & Italian Jesters before him have been crossing a well-trodden path between Italy and the UK ever since. On this occasion, Pirovano’s English tour of Dario Fo’s Francis The Holy Jester began in July at the International Medieval Congress in Leeds and concluded in September in London. (see review). Of course, it has to be remembered that often jesters were compelled to leave Italy and France, fleeing the persecution of the counter-reformation. In his address in March this year for UNESCO’s World Theatre Day, Dario Fo declares to his audience how it requires artistic courage to work in the theatre. He quotes from counter-reformation propaganda that recognises how much more powerful theatre is even to the printed word: “Evidently, however, while we were asleep, the devil laboured with renewed cunning. How far more penetrating to the soul is what the eyes can see, than what can be read off such books! How far more devastating to the minds of adolescents and young girls is the spoken word and the appropriate gesture, than a dead word printed in books. It is therefore urgent to rid our cities of theatre makers, as we do with unwanted souls”.

You might be forgiven to feel that such a view seems somewhat paranoid and anyone wholly fascinated with the plays of the Middle Ages and Renaissance might fall into the trap of fighting past wars instead of addressing issues in the present. With this in mind, I listen as Mario explains his current plans to produce monologues by ‘Ruzzante’, a stage character of Angelo Beolco (1496 – 1542) who, Dario Fo argues, is the true father of the Venetian comic theatre. Mario hopes to launch the new show based on Ruzzante Returns from the Wars, as he did Francis the Holy Jester, at the Edinburgh Fringe.

The comedy shows Ruzzante returning to his native village, having deserted from the army out of cowardice. Once home, he finds his wife has left him for a bullying ruffian. However, he manages to regain her interest by bragging to her that he’s a war hero. She is somewhat impressed but not enough to go back to him. She explains how she would have preferred if he had been wounded and maimed to prove his love for her. Ruzzante goes on bragging to his friend Menzante about what a hero he is and turns cowardly motives into heroic ones. He tries to convince his friend, for instance, that the beating he gets from his wife’s new man was inflicted on him by 100 men. He fails, of course, and the play ends with Ruzzante proudly protesting that he does not care about his timidity!

All the themes of the Commedia dell’Arte are present, even if the well-known masked characters of the 18th century such as Arlecchino, Brighella and Pantalone are not. There’s the fool playing cowardness… heroically; there are lovers playing at love… lustfully and the central character, Ruzzante, an anti-hero, accomplishing little more than basically surviving. Most notably, there’s the presence of a strong woman who, like all the female characters of the Commedia, represent womankind being just as manipulative as men. Written before 1528, this shows that Beolco’s Venetian theatre used women in its company at least 140 years before the first English actresses trod the boards of Restoration theatres in the 1660s.

But for Mario Pirovano, Ruzzante Returns From The Wars is not about the past but the present. Most importantly, it’s about the on-going absurdity that men continue to return from wars to homes and societies who think the conflict is over when their men return. In truth, however, the combatants face more conflict and pain back home as war changes all before it, both for those who go to battlefields and those who remain at home.

Now, what should we do about that terrible fact? Should we cry about it? Clearly, that’s proven to be the case. But what if, through the jester, we also find a reason to laughing at the nonsense war represents, and through that knowledge, we give the whole terrible situation a good poke it in the eye!