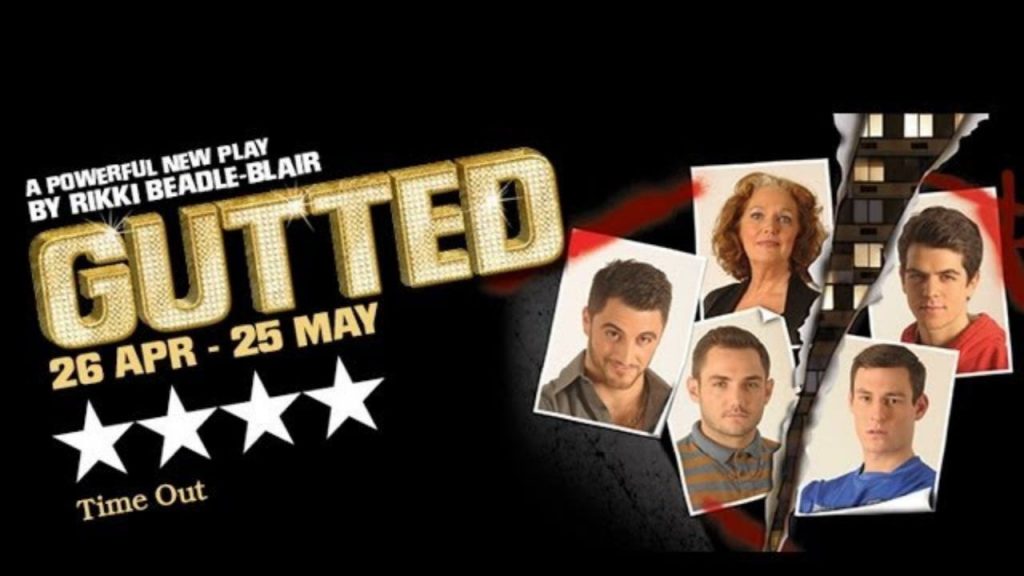

Genre: Drama

Venue: Theatre Royal Stratford East Gerry Raffles Square, Stratford, London, E15 1BN

Low Down

In the most straightforward sense, Rikki Beadle-Blair’s new workGutted has all the hallmarks of a classically crafted piece of ‘epic theatre’. Its episodic structure is linked as tightly and economically as any Brechtian drama.

The play’s characters from South London are the Prospect family. They are consciously working class, a perspective tying them directly to the epic ‘political’ theatre form that borrows much from Marxist views on class warfare. And as Brecht brought together class and crime on London streets in Threepenny Opera, Rikki Beadle-Blair makes similar links within the lives of the four Prospect brothers through their encounters with petty car theft and going to jail.

The playwright’s use of Brechtian techniques is also seen in the iconic naming of characters: the surname ‘prospect’ is a clue, as are the Christian names ‘Matthew’, ‘Mark’, ‘Luke’ and ‘John’ as radical forms of truth bearers, like their namesakes, the four writers of the Christian gospels. Through these names the playwright sets up a sense of they can be identified as essentially storytellers. They are characters in a play, they both directly address the audience and speak naturalistically to one another and to other characters in the drama: to their mother Bridie, their wives and girlfriends.

In this production, Rikki Beadle-Blair is also its director, designer and composer. He shapes each detail of the narrative in a performance space flanked by tall mirrors, with four simple projection screens suspended halfway between the back wall of mirrors and centre stage. The projections are mostly photographs of the four men as boys, taken in school uniform / school photo form or taken with their girlfriends. I notice the clean look of the characters in the photos in comparison to their more crumpled appearance on stage. One panel of the four screens displays text naming or commenting on the scene below. The non-naturalistic performance space is mostly bare, with occasional tables and chairs moving on & off stage, whenever there is a need to define locations such as a restaurant or a backyard house party.

The story around the Prospect boys shows the everyday happenings in their lives: it begins with Matthew, a professional footballer, in a rehab clinic. As the family assemble in the hospital reception area to pick him up and bring him home, where they’ve organised a ‘welcome home’ party, the story moves between the present and the past to reveal to the audience the events which lead to this point.

The extraordinary thing is that while at a conscious level you view the ordinary happenings of the four men, their mother, their girlfriends and wives, something else happens in the telling of their stories. They are changed and you are changed. The personal is political.

Review

While it would take more than the length of this review to describe the wonder of what I saw performed on stage, I will describe the areas of Rikki Beadle-Blair’s Gutted which I came to admire the most.

To begin with, I couldn’t help being impressed with playwright’s use of ‘working class’ language. It seems to me to be done in the most remarkably poetic way, especially through its swear words and its use of silences. The authenticity of a so-called ‘limited’ working class vocabulary is completely re-thought! This is not a play for the faint-hearted, the dialogue sparkles with swearing. Unfortunately, it means that schools, for instance, will not be able to bring students under-16 to see it. Ironically, it is the most well-crafted play which any teacher is likely to show young writers about the use of language itself.

It is also ethically above reproach as it comes from the playwright’s exemplary respect and empathy for his characters. It is not possible to see the Prospect family as anything other than worthy of admiration for the gallant way they make the small but life changing difference to situations that we come to discern in the play as child sexual abuse and physical violence.

At the same time, there is no hint that as an audience we are put in a position to deal with the abuse and violence in anything but an appropriate way. Remarkably, this is because the need to change is not removed from the Prospects but clearly seen to be their individual and collective responsibilities.

For instance, Matthew’s relationship with his girlfriend Lucy is dangerously dysfunctional as it lives on the cusp of gratuitous sexual wish fulfilment & the abuse of young boys. It is Matthew and Lucy who end their relationship and come to understand that ‘some people shouldnever be together.’ She is too broken for him and he for her: neither have enough personal strength to deal with each other’s pain and dysfunction, while, thankfully, they are not so damaged that they don’t know that they are in danger of becoming even more dysfunctional if they continue being with one another. At the end of the play, when his mother, Bridie, invites Matthew to bring Lucy to breakfast with the family, Matthew prophetically and simply states “I can’t Mum. Lucy can’t make it.”

The line drawn in the play between right and wrong is paradoxically continuously interrogated and at the same time immutable. Therefore, while the audience observes how Lucy and Matthew end their relationship for good reasons, it also moves on a journey with brother Mark’s relationship with his wife Janine, John’s with his Muslim girlfriend Sunai, Luke’s with the transgendered Frankie and Bridie with the boy’s deceased father Eammon, a drunk and child abuser. Each relationship is in some sense iconic and therefore placed on stage so we can realise through them the truths around ending abuse and moving towards fulfilling a need for human intimacy and belonging.

The radicalness of the play, however, is in its ability to position the audience to see the ‘bleeding obvious’ and more. Mark must deal with Janine’s physical punishment of their five year old twins and John must deal with his lack of respect for women and his misuse of the Qu’ran through his relationship with Sunai. Most importantly, Bridie must acknowledge that her silence enabled her husband to harm her children and make their life hell: especially for her first born Matthew, whose exceptional skill as an athlete brought him to the attention of the local football club, Millwall, and onto whom the father transfer his aggression as well as his own desires.

In a most wonderful irony, Luke’s relation with the transgender Frankie seems to be the happiest and most straightforward of all the relationships presented. Luke simply understands Frankie’s vulnerability and the hazardous life ahead for her. He will be her knight protector. Frankie understands Luke’s need to make sense of the seemingly ambiguously moral situations in his life. She is more than able to set him straight about what really does and doesn’t matter.

There are many more elements of Rikki Beadle-Blair’s Gutted which are impressive, not the least is the play’s sense of humour. It is hard to imagine that a play that deals with child sexual and physical abuse in such a candid way should give rise to such deep and genuine laughter as you hear in the audience throughout the performance. Like everything else in the play, it is not haphazardly or savagely done at the expense of anything or any one but arises from the truly incongruous, ridiculous and inappropriate moments in the Prospects’ world. At times, laughter is also the only response other than despair.

The levity in awful situations is alongside some of the most moving monologues I have ever heard in performance. Matthew’s eulogy at his father’s funeral hits the mark in revealing the regrets of a young man who knows he deserved better than what his father metered out to him. Death now ended any chance of changing that relationship:

I suppose I’m supposed to forgive him. And suppose what I’m supposed to do today is ask you lot to forgive him too. It’ll take you a while. But what the hell, think about, yeah? I will. Tell you what – next time we’re all together – next wedding, christening, funeral – whoever’s forgiven him by then… speak up, yeah? … Cool

Matthew also describes his father as the Irish boy who came to an England in which landlords put the sign ‘No dogs, no blacks, no Irish’ in their windows, teachers mocked his Irish accent, kids threw potatoes at him and the school caretaker spat at his face in front of the whole assembled school. He goes on to say that he father lived his life hating dogs, blacks and the Irish worst of all. But as a son, he know it was his hatred of everything, including his own Irishness which diminished him ….

Dad was a cunt. Everybody here knew him, yeah? Worked with him, drank with him, was related to him, met him. Then you know. Dad was a cunt. And now he’s dead, And it’s time for me to step up and be a man. How the fuck do I do that? We never got round to that little chat.

The capacity to love is expressed in Gutted in real terms. Love means understanding and respecting the vulnerable, including areas of vulnerability within yourself. Fathers should protect their children. So Mark steps up and does just that for his own children when their mother hits them: and he will do it even if that means losing the wife that he loves.

Nor should mothers be absolved from facing up to their own selfish and cruel reasons for keeping the status quo. Bridie’s characterisation in the play is a revelation of a woman’s responsibility in living in a kind of dream world in which she continued to apply mudpacks, have her hair done and wear fur coats even while her sons are being beaten and abused by their father. Yet her doing so also gives her sons a living example of how to keep going despite the presence of pain: all they needed to do was call on her.

Experiencing Gutted gives me a renewed appreciation of the meaning of ensemble. The Prospects played James Farrar as Matthew Prospect; Frankie Fitzgerald as Mark Prospect; Jamie Nichols asLuke Prospect Gavin McCluskey as John Prospect and Louise Jameson as Bridie Prospect were in every sense a tour de force. Their control and presentation of the crafted and nuanced working class South London dialogue was magnificent. But this was a play which also redefined the meaning of a minor role: Dominique Moore as John’s partner, Sunai; Jennifer Daley as Matthew’s girlfriend Lucy; Sasha Frost as Mark’s wife Janine and Ashley Campbell as Luke’s girlfriendFrankie each defined their roles with every attention to detail. Ashley Campbell adds much to the meaning of the play through his role as Moses, the imprisoned black kid that converts John to Islam.

If I could give Gutted more than 5 stars I would! It is an exceptional play, worthy of comparison with Jez Butterworth’s Jerusalem in showing a view of contemporary life that is screaming to be seen and understood. While Butterworth gave us a view of the indigenous English dispossessed from his and her own land, Rikki Beadle-Blair gives us a view of how individuals and families are implicated in creating dispossession in contemporary urban settings. But that’s only half of it, as different qualities of the same characteristics – a mother’s touch, a father’s embrace and a young person’s talent – are shown inGutted to also have the power of changing the world for the better. I hope that the playwright, cast and crew get every chance to show the play globally!

Reviewed by Dr Josey De Rossi Thursday 2 May 2013

Website :

stratfordeast.com